[ Silence ]

[ Silence ]

[background conversations]

Well, good evening. And welcome to the United States

Geological Survey public lecture. I'm Diane Garcia, and I work with

Science Information Services, and I'm glad to see you all here tonight.

Before I start on introductions of our speaker tonight,

I just want to remind you that we will be having a November talk on

November 30th – the last Thursday of the month and the last day of the month.

And it's on sea otters – confessions of a keystone carnivore.

There are fliers at the back table, so please grab one so you can

have it as a reminder. We'd love to see you here

November 30th to hear Tim Tinker talk about sea otters.

But now what we're really here for is to hear a talk on global trends in mineral

commodity supplies, and it's going to be presented by Dr. Steven Fortier.

Steve joined the U.S. Geological Survey in the role of director, National

Minerals Information Center, in 2014. Steve came to USGS after 18 years

in the private sector in industrial minerals mining and processing.

Steve holds Ph.D. and master's degrees in geological sciences

from Brown University and a B.A. in geology and chemistry

from the University of Maine-Farmington.

His research interests from the early part of his career

involved fundamental studies of mineral fluid interactions as well as

numerous collaborative studies involving stable isotope applications.

He's also an inventor or co-inventor on four U.S. patents.

During his many years in industry, his focus was on ground and

precipitated carbonates, kaolin, fused silica, fused alumina,

sintered mullite, and calcined bauxite.

His experience with the commercial applications of

these materials includes paper, performance minerals, ceramics,

abrasives, refractories, and oil field minerals market segments.

So the United States Geological Survey's public lecture is pleased

to bring you a talk on mineral commodity supplies.

And I'm going to ask, as always, that you please hold your questions until

the end of the talk. But let's give a nice, warm applause and welcome to Steve.

[ Applause ]

- Thank you, Diane. - Thank you.

- And I'd like to thank also the organizers of the USGS public lecture

series for inviting me to come to speak. It's ways a pleasure for me to come and

talk about the work we do at the National Minerals Information Center.

It's really surprising to me that a lot of people, even within USGS,

don't really know much about the National Minerals Information Center.

It has a reputation as being one of the best-kept secrets in the U.S. government.

But I can assure you, we are working diligently to change that.

I'm going to talk today about global trends in

mineral commodity supplies and why we think that's important.

But I'm going to start by talking a little bit about who the NMIC is and what

we do and why we think it's important to kind of set the stage for that.

So having spent most of my career, at least the last couple decades,

in the private sector, I still kind of think about

the work we do in terms of a business model.

And one of the things I really like about NMIC is it has a very good

business model in the sense that we have a very well-defined mission.

We have a very well-defined product portfolio.

A very well-defined customer base. And I'll talk a bit about each of those.

Our focus is operational, so we really are a mineral information –

the mineral information function in the U.S. government.

We are a production shop. We work on monthly, quarterly,

and annual cycles, so our product cycles are coming out

on a regular basis, much the way you would in a – in a business.

And I can say, I think, without fear of contradiction, that we consistently

deliver results. It's one of the things we pride ourselves most on.

Our products are widely anticipated and

very well-received and very widely used and cited.

So a bit about the mission and some of the stakeholders

that depend on us to deliver on that mission.

We have a very simple mission. It's to collect, analyze, and

publish information on domestic and international supply and demand

for non-fuel mineral and materials – essentially,

the U.S. economy and national security.

And you will see, I think, as we go through this, what that means in practice.

You know, we are the fact-based mineral information function in

the U.S. government. We don't make policy. That's for others.

So our objective is to provide decision-makers in the U.S. government

the information they need to ensure that the U.S. has

an adequate supply of minerals and materials to meet our needs.

So for example, you see along the bottom there some of the

other government entities and organizations that depend on our work –

the U.S. Senate and House. We get requests routinely from Congress

for briefings on a variety of issues relating to mineral raw materials.

We've just been asked by the U.S. Senate to provide a report by

spring of next year on the USGS perspective on the status

for domestic mineral resource assessments in the U.S.

and recommendations about what we need to do going forward.

So this would be a major focus of our work in the coming months.

But we've also worked directly for other government entities such as

the Office of the President, OSTP – we work directly with the

Department of Defense, particularly the Defense Logistics Agency.

I'll talk a bit more about stuff we do for them.

And also the intelligence agencies are consumers of our information,

as are the Departments of Energy, State Commerce, and also we provide

information directly to organizations such as the Federal Reserve Board.

So you might not think of all of those agencies when you think about the

supply of mineral raw materials, but in fact, mineral raw materials are

so fundamental to everything we do and so fundamental to our standard of

living that all of these other agencies have some component of their

own missions that require them to understand the supply and demand

of mineral commodities and whether there are risks to that supply

that could impact the interests of the United States.

So the scope of our mission within the center is really quite broad.

I think it's as broad or broader than any other comparable

organization in the world. You see here in this periodic table

the commodities that we cover in some way, shape, or form –

so either as an element or a metal or a compound – mineral.

So pretty much the bulk of the periodic table of commonly occurring elements.

We also have a very broad international coverage,

and we are sometimes asked why we have such a global scope.

I think some of the slides I will show you will point out why that's important.

We produce more than 700 publications annually

on the cycles that I mentioned earlier.

And we've got a continuous record of mineral information going back –

particularly for domestic production in the United States – to the year 1900.

So we've been – the NMIC or its agency predecessors

have been doing this for more than 100 years.

Some of our publications will probably be familiar, at least to some of you.

Probably the most prominent are the Mineral Commodity Summaries.

This comes out every year at the end of January.

It is the earliest look at the prior year mineral industry production

and consumption statistics available anywhere.

It's widely anticipated and cited. Senator Murkowski and others

in the Senate routinely cite our publications in their –

in their comments for the record in the U.S. Congress.

But we also produce the Mineral Yearbook series,

Mineral Industry Surveys, and Metal and Nonmetallic

Mineral Industry Indexes, as well as a number of

special publications, which is increasingly a focus of our work.

The analysis piece of our mission is becoming more and more

important as we – as we move forward.

So what are some of the kind of macroeconomic geopolitical trends

that are kind of driving our concern about security of supply of mineral

commodities and, I think, amplifying the importance of what we're doing?

Well, in some ways, the kind of levels of production that we're seeing are

historically unprecedented. So here's an example using iron ore.

This is from our historical data series going back to the year 2000.

This is world production of iron ore here, and you've got, in red, Australia.

And then you've got Brazil and China. They're big producers.

The U.S. is basically flat here.

But the growth in the production of iron ore over this period of time,

and the absolute volumes that are being produced, are staggering.

There are more than 2 billion tons of iron ore being produced annually every year.

I'm quite confident that that's never occurred in human history before.

[laughter]

So you see the very rapid ramp-up of production capacity

in countries such as Brazil and Australia to support that.

And so the growth has been very rapid. It's been dominated by China.

And we anticipate that there will be continued demand growth for the

rest of the world for reasons I will talk a bit more about in a minute.

But if you look at some of the numbers, world production is up by 140%

over this period of time. The production volumes in

Australia have grown by a factor of 5,

Brazil by a factor of 2, and in China by a factor of 4.

So, you know, it's been basically flat in Europe, Russia, elsewhere –

iron ore production. So where's all this iron ore going?

Well, it's going pretty clearly into the Chinese steel industry,

which leads to observations such as this, which is that, in the years of the

21st century, from 2000 through '14, China has produced as much steel –

about 7 billion tons – as the U.S. did in the entire 20th century.

So the scope of development and consumption of mineral

commodities in China is absolutely enormous.

And it has impacted the entire rest of the world and the way we view our

supply situation and vulnerabilities to potential disruption in supply.

It's impossible to overstate how important this is.

What happens in China impacts the entire rest of the world.

And so it's something we need to pay a lot of attention to.

So what is – what is behind this? Well, people normally think about this

in terms of population growth. And it's not just population.

I mean, China had a very large population long before they became

the largest producer and consumer of a whole range of mineral commodities.

It really is about middle-class living standards and the migration of

people to middle-class living standards. So there was a study that was published

some years ago now where they were projecting that, between 2009 and 2030,

that as many as 3 billion additional people globally could be moving into

what are considered broadly defined as middle-class living standards.

So with middle-class expectations about smartphones

and computers and automobiles and jet aircraft.

And really that big run-up in commodity consumption that you saw,

as an example, in the iron ore data was driven by literally hundreds of

millions of Chinese citizens achieving middle-class living standards.

And there are projections that this is going to continue with the largest

increases being in the Asia Pacific region – so India, Southeast Asia –

but also large increases in East Africa and elsewhere.

Europe and North America and these projections are basically flat

or declining in absolute numbers. And with a shrinking global share.

So as these citizens from other countries increase their living standards,

we can expect that they're going to require a lot more

mineral consumption to meet their needs.

This is why we think, in the long term, that the kinds of

growth in demand – although maybe not at the same rates –

are going to continue to be very large as we go forward.

The other big thing that's happening is that technology is becoming

much more complex. Right, so I think, you know,

most of us – or at least some of us [laughter]

can remember when mobile phones looked like this.

And they had far fewer elements that were in them in those days.

Smartphones have a lot more.

And this is true of virtually all modern electronics.

So the applications in material science are getting more and more specialized.

And so elements that we never thought about using before,

we are now using in increasing quantities to the point where we are –

you know, we are utilizing large fractions of the periodic table.

Whereas, we weren't only 20 years ago or so.

And so this is one of the reasons I always point to when people ask us,

well, why do you cover all these commodities?

Well, we're using them all. And so we need to know

where we're going to get them from and whether we're going to continue

to be able to get them. And that's becoming increasingly important.

So just as an example of the kind of work that we do for

other government agencies that relates to security of supply issues – so we

work very closely with the Defense Logistics Agency-Strategic Materials.

So these are the folks in the Department of Defense who are

responsible for maintaining the national defense stockpile.

So they do scenario analysis and evaluate various conflict scenarios

and what the impact would be on the U.S. readiness to

be able to meet such challenges. So we provide them very basic

foundational information that go into their models about the latest

production capacities and production volumes for various countries.

They put that into their models, and they do their scenario analysis

to do the annual material plan and the biannual report to Congress on their

recommendations for how we adjust the national defense stockpile.

But part of their mandate from Congress is in their definition

of strategic and critical materials in the Stockpiling Act.

And it is – that part of it is that these are materials that are not found or

produced in the United States in sufficient quantities to meet such need.

So that leads us directly to a statistic that we report every year in the

Mineral Commodity Summaries, that is, the net import reliance,

which is basically you can think of as the amount of material that we

import to meet our domestic consumption needs.

So if we don't produce anything domestically, whatever we consume

is being brought in from outside. We are 100% net import reliant.

The number of those materials has been increasing for decades.

I'm going to show you some data on that in a minute.

But this is what this chart normally looks like every year when it

comes out in the Mineral Commodity Summaries.

This is difficult to read, but many of you may have seen this.

But if the bar is fully across here, we're 100% net import reliant,

and it decreases as we go down.

This is probably one of the most famous graphs that USGS produces.

Senator Murkowski has used this repeatedly in her comments

to her colleagues in Congress. And so it's something that people

look at very closely and anticipate coming out every year.

So a couple of key publications that [coughs] – excuse me.

A few guys on the plane got me, I think.

A comparison of U.S. net import reliance going back to 1954.

Excuse me. I'm going to have to get a drink of water here.

Otherwise – if you just bear with me. I've got some in here.

Okay. That's better. So we did this a couple years ago – 2015 –

published this report on U.S. net import reliance going back to 1954.

And looking at 30-year slices up to the year 2014.

And then a second one on the assessment of critical minerals that

we did for the National Science and Technology Council in 2016.

I'm going to talk about each of these in some detail.

So here's what the geographic distribution

of import sources looked like in 1954.

And you can see the categories here. Between seven and 12 commodities

coming from Canada, for which the U.S. was greater than 50% net import reliant.

Significant numbers also coming from Mexico, Brazil, South Africa.

[coughs] Excuse me.

So it was a fairly modest dependence on

imports 60 years ago compared to the present day.

And a lot of that material was coming from the western hemisphere –

so Canada, Mexico, Brazil – countries that share borders with us

and trade relationships in the case of Canada and Mexico.

And so, you know, from a security supply point of view, a fairly low risk.

If you fast-forward to 1984, you can see that we've got many more

commodities that are now in the greater- than-50% net import reliance category.

We've got an entirely new category – 13 to 18 commodities

coming from Canada – still our largest supplier.

Increase in the number coming from Mexico up to the seven to 12 range.

But then increasingly coming from further abroad –

much longer supply chains. What was then the USSR,

also China and Australia as well as continued supply

from South Africa. That was in the mid-'80s.

If you fast-forward to this century in 2014,

the situation has deteriorated markedly from this perspective.

So we are now – have another – still another category of number of

commodities that we are greater than 50% net import reliant for.

And this is kind of a threshold for us.

So above that level, we are importing more than half of what we are

consuming domestically relative to what we're able to produce domestically.

And that's a kind of threshold that we look at to – as a kind of

trigger for things that we should start to be more concerned about.

But again, you know, considerable numbers of materials coming from the

western hemisphere, but our dependency is now very clearly very global.

And particularly dependent on China

to a degree much larger than we've ever experienced before.

So to sum up the net import reliance piece, this is a long-term secular trend

toward increasing reliance on other countries for many of the mineral

commodities that are essential for our economy and national security.

Supply chains are increasingly global with long logistics channels.

Canada and Mexico remain major suppliers. This is important.

This is a way of mitigating our risk. The more materials we can get from

Canada and Mexico, who are adjacent nations and with whom

we have longstanding trade relationships, the better off we are.

The risks are inherently lower.

So we should, I think, be a little bit careful about how we approach

our relationships with our major trading partners.

Without getting too political.

China is a single-largest supplier of many of these mineral commodities.

And if we think of – we look at what happened in what we reported for 2016,

the U.S. is now greater than 50% net import reliant for 50 mineral

commodities. This is more than half of the commodities that we cover.

China is a major supplier for more than half of those.

And we are 100% net import reliant for 20 of those 50.

So, you know, I think, by any objective measure, our reliance on

mineral commodities from other countries has reached an

unprecedented level, which is not in all cases

an indicator of risk, but it certainly can be a risk.

And it's one of the reasons why we look very carefully at this and report this

information every year and make sure that policymakers get this information.

Because it is – it is a source of concern.

I think also – the last bullet here is, for me, one of the most important.

It's taken 60 years for us to get to this position.

And to think that we will somehow, magically, quickly or easily reverse this

is magic thinking. I mean, it won't happen. Mining just does not work that way.

And so, while we do need to, I think, do more to encourage and enable

domestic mining, we should not think that somehow it's going to

very quickly change the situation. So there need to be other strategies

that we adopt to help mitigate some of our risks.

So this net import reliance immediately leads to, you know,

consideration of some of the ways that you can measure the risks

that are associated with sourcing materials from one country and another.

And the way we do it is to use the World Bank governance indicators –

the worldwide governance indicators from World Bank.

There are a series of six different factors by which they quantify the risks for

various countries – so rule of law, political stability, et cetera.

They sum those all up, take the geometric mean, and then they assign a score.

So the red colors are higher risk, and the green are lower.

So you can see, for large parts of the world,

there's lots of yellow, orange, and red. Much more than we would like.

We'd like things to be green like Canada or Australia or the U.S.

But much of the rest of the world is not that way.

And so – and in particular, you know, central Africa, the Middle East,

are hotspots for governance issues and have inherently higher risk

if you are depending on those countries for significant quantities of materials.

You know, China is sort of in the middle of that range.

But in any case, this is a metric that we can use to weight our measures

of concentration of production to make a supply risk metric.

And that's what we've done in some of our modeling.

To look at a specific example of what this means, we can look at tantalum.

We had a tantalum task force a couple years ago because of interest

from the U.S. Congress. The House and Senate were both

asking questions about tantalum. The Defense Logistics Agency was

being – had an inquiry from GAO – were also on here. So GAO was interested.

DLA was interested.

And they were asking questions about whether the U.S. government

was doing what it should or was properly evaluating the risks

to the supply of tantalum in the United States.

And so we looked in detail at this issue and published three papers on this.

You might wonder, well, why are we interested in tantalum.

If you have a smartphone, you have some tantalum with you.

So tantalum is, as it turns out, from a material science perspective, very good

at being a capacitor. And capacitors are in every electronic circuit there is.

And, because tantalum is a very good material for this,

you can make capacitors very small, which is quite handy if you need to

have a very powerful electronic device on your belt.

And so tantalum is in virtually every electronic circuit that we use these days.

And if you look at the supply situation for tantalum, going back to the year

2000 through 2014 in this publication, what you see is that, at the turn of the

century, the bulk of production was actually coming from

Australia and Brazil. That's the blue and red here.

But the production in Australia has dropped off dramatically since then.

And since about 2006, supply had began to be dominated by the Democratic

Republic of Congo and Rwanda. So this is why, in part, the Senate

and the House were interested in this. These are Dodd-Frank countries.

When I came to USGS, I didn't know that USGS

had anything to do with Dodd-Frank.

I thought it was about transparency in banks, which it mostly is.

But there's a section in Dodd-Frank – next to the last one, I think, that says

transparency also applies to mineral supply chains, particularly those

surrounding the Democratic Republic of Congo, and that companies that are

sourcing materials from those areas need to do due diligence on their

supply chain to ensure that they're not getting materials from

armed groups which are controlling much of the production there.

But there's been a big shift over this period of time – and this is a period

of only 14 or 15 years – where we have gone from supply being dominated

by Australia and Brazil to supply being dominated by Democratic

Republic of Congo and other African countries where there's

significantly higher governance risk, as we saw here.

And we've gone from industrial mining and transparency of supply

chains to artisanal mining and a lack of transparency in supply chains.

There's a big change in the production of this material

over a period of 15 years that has led to significantly higher risk.

Tantalum is widely regarded as a critical mineral.

The U.S. is 100% net import reliant.

So these are the kinds of trends that we need to be monitoring to understand

what's happening in the global supply in order to be able to evaluate

whether we are at risk to disruption in the supply that could be

quite damaging to our economy or national security.

So the second of these key publications, as I mentioned before,

is a report that was written principally by people in my center with some

help from the Department of Energy. But it was written for the

National Science and Technology Council of the –

for the Subcommittee on Critical and Strategic Mineral Supply Chains.

And this basically describes the development of a screening

methodology we developed to try to evaluate the trends in our

mineral information data to see if we can identify behavior

that suggests that we could have a supply risk emerging.

So here's the kind of output that we get from this model.

So what you're looking at here is a periodic table that basically shows a

time series going back to the mid-'90s through, at this point, 2013.

We've got 2014 data in here now. We're about to put in 2015 data.

But these are a criticality indicator, which is a sum of a number of

different components, which I will show you in a moment.

Not getting into great detail on that, but you can see, as you go back in time

or you go forward in time, for your favorite element –

so peaks and valleys in criticality as measured by these metrics.

And so each of these trends is telling us something about what was happening

with supply and demand for those materials as we go forward in time.

So we believe that, by looking at these trends and tracking these trends –

and we are ideally situated to do this because we produce

this information every year as part of our normal product cycle.

And so we can – we can set up these models, and we can update them

every year and try to identify emerging supply risks from this.

So we've done this for virtually all of the materials

that we cover, or at least most of them.

For some things, we've got more information than others.

So for example, for copper, we can do it at the mine level,

we can do it at the smelter level, we can do it at their level of refining.

We can do ferroalloys, which is another important set of commodities we cover.

And then we've got some that are – that are basically just minerals –

potash, for example. The rare earths are here.

But so we're covering much of the periodic table that we cover

as a normal course of our work and using that information in this model

to try to anticipate problems coming in the supply chain.

So here's what this looks like for rare earths –

the Early Warning Screening Tool Application to rare earths.

There are three different components to this.

One is the supply metric, which is basically country concentration

times the governance risk. So I showed you the

governance risk from the World Bank world governance indicators.

Country concentration is simply the fraction of production

that is in a particular country. So if – for example, for rare earths,

China is producing 90%, then the country concentration

is going to be very high. And so then there's a demand metric

that tracks sort of total global consumption.

And then a price metric that basically looks at price volatility.

And then we roll these all up into a single metric for the

criticality indictor and take the geometric mean of these

components, and that's the criticality indicator.

So if you look at this, what we would say is the following.

Going all the way back to the mid-'90s and up until, you know, the turn of the

century, this metric for supply risk was steadily increasing for rare earths.

And so if we were watching – if we were monitoring this commodity

using these metrics, that should have been a signal to us that something

is changing pretty radically that we need to be aware of and potentially

do something about. All right, we didn't.

And in 2010, we had a shock from China where they –

after a territorial dispute with Japan, threatened to

cut off the supply of rare earths. Price spiked up.

Everybody got in a frenzy. But, you know, you could see this

kind of behavior in these metrics for the supply risk and for the price risk.

Actually, price was trending upward well before the crisis actually occurred.

So we believe that, if we were tracking these things, we can see

behavior that could indicate that we have an emerging supply risk and that

these are useful metrics for us to track in order to be able to anticipate those.

So here's the – is the famous rare earths story in terms of production volume.

So the U.S. used to be the major producer.

This is Mountain Pass. We already talked about that this afternoon.

And then the Chinese started to come in, and so, in the mid-'80s – and now the

dominant producers of rare earth and are very deliberately moving in the

direction of controlling the entire supply chain.

As we had Mountain Pass coming back in in the wake of the crisis in 2010,

but they've since stopped.

I understand that they may be starting up again, having been purchased.

But, you know, the mix of rare earths at Mountain Pass is not ideal for the

kinds of things that we really need. There is neodymium there,

but there's very little dysprosium or praseodymium, which are important

in magnets as well as neodymium. So we really need additional rare earth

capacity to come online in order to mitigate this very large production

concentration in China that is a very clear risk to materials

that are absolutely essential for a whole range of technologies

of commercial and national security use.

So some other things that we could look at.

So here's the rare earth story. And so this dip down, we just

pointed out – okay, this reflects Mountain Pass and Lynas coming online.

If we extended this out with additional data, we'd see this

start to trend back upward. Although Lynas has basically

stabilized their operations in Australia after some rough years economically.

They are being supported actively by the Japanese,

who are determined to diversify their supply of rare earths.

But the interesting thing about the Lynas production is that it's mined in Australia,

it goes to Malaysia to be processed into concentrates.

But a lot of that material is actually flowing into China to be made into

metals and other compounds. There are other flows going to Japan,

but because China dominates the mining and concentrate processes for rare earths,

they have also started to dominate metal production and compound production.

They are increasingly doing the research that's required

to fuel advances in those technologies.

And so it's not enough to just be able to mine and concentrate minerals.

You've got to think about the rest of the supply chain.

And this is something that we are increasingly focusing on

in the NMIC with our U.S. government agency partners.

The defense agency – Department of Defense and the intelligence agencies

are particularly interested in this, and we are working with them on that.

So bismuth, which is commonly – more and more commonly used as a –

as a replacement for lead, and this ramp-up is clearly related to increased

production concentration in China. Then cobalt, which is an element of

a great deal of interest for lithium-ion batteries – it's one of the most common

elements that are – that are needed for cobalt and is likely to be –

come in much higher demand. And most of it is coming from

Democratic Republic of Congo again, which, as we said before, has clear

governance issues. So this is one that we are watching very closely

and that we need to keep an eye on.

And then, you know, you see tantalum spiking up here as well.

So we are – we are going to be updating these numbers every year

and using them to try to anticipate and alert people in Congress and

other decision-makers to what we perceive as being emerging risks

and hopefully get people to actually do something.

My sense is that there is a greater interest in that now because some of

these things are becoming obvious, that they are increasingly –

that we increasingly are at risk and that we need to have

mitigation strategies for how we would cope with these risks.

So just to sum up, how are you using global trends in mineral

commodity supply chains? So we have been able to identify

trends and factors that affect the supply and demand of mineral commodities

on a range of different time scales with a range of different metrics.

Using time series analysis is a very useful tool for screening over a broad

range of mineral commodities to identify potential emerging supply risks.

That in itself does not mean that they are critical.

Just because they pop up on our metrics doesn't mean they're critical minerals.

We have – we are, I think – been pretty clear with people,

although people don't always accept it.

People want us to produce lists, okay? They want a list of critical minerals.

In our view, lists have some utility, but a list of critical minerals really

depends on who's asking the questions.

So if you're Halliburton, you probably think barite is a critical mineral.

If you're General Electric, you probably don't think barite is very critical at all.

If you're Department of Defense, you've got a completely different list.

So we believe that, in order to really understand whether something is

critical and represents a supply risk, we need to do follow-up studies

to really understand the factors driving the changes in the metrics we see.

So just having a high number on a metric on some model

doesn't mean that it's a supply risk.

So deep-dive studies as follow-ups are really what allow us to determine that.

And, again, we are, I think, uniquely suited to do that kind of work

because we have experts in commodities and countries that

work in our center that can really do that analysis.

We have that capacity in a way that very few others do.

I say that for a number of reasons.

One, our coverage is very broad in terms of the commodities we cover.

Our scope is global. And if you looked at those net import

reliance charts, it's pretty clear why we have to have a global scope.

We can do country-specific analysis, so we can analyze things from the

perspective of the United States. We can also analyze things

from the perspective of competitors or potential adversaries.

Our data are authoritative. They are widely viewed

as the gold standard globally. Everywhere I go and speak,

people come up to me and say, we use your data all the time.

And then they say, can we get it faster? [laughter]

And actually, we've done something to make that possible.

We are – we are getting data, at least, quicker.

The publications that accompany them are still slow, but that's another matter.

It's important to do this in a dynamic way.

You know, mineral criticality is not static.

And a lot of the studies that have been done have been a snapshot in time,

but things change markedly over time. We're now in the third annual cycle

of doing this kind of analysis – the screening analysis.

And in the second year of the cycle – second year, we were able to

demonstrate that you can – you can detect statistically significant

changes year on year using these metrics. And what we've seen so far,

usually we can trace back to changes – significant changes in production

in a commodity that is highly concentrated in a particular country.

So if you have something that's very highly concentrated, and you get a

significant change in production, it shows up very clearly in our metrics.

And so the sensitivity is something that we have evaluated

and are starting to get a better feel for.

But it is dynamic, and it needs to be done on some kind of schedule.

The Europeans are doing theirs every three years.

We are doing ours every year.

We want to – we want to look at trends. We don't – I mean, people want lists,

and we'll give them lists if they want lists.

But we are really focused on trends because we think

it tells us a lot more than just making a list.

And our model seeks to balance rigor – that is, we need to

have metrics that are actually telling us something significant

that relates to some physical reality – with the availability of data.

So there are lots of complicated metrics that you can use to evaluate criticality,

and people have used them. But if you can't get data

for a broad range of materials, they're of limited utility.

And so it has to be rigorous enough so that you're getting a –

you're getting a signal that's real, but you need to be able to get the data,

which means it needs to be readily available.

And our data, which we produce every year, are that.

And so we believe that that's another reason why we are

uniquely suited to do this kind of work.

So the kinds of data we're talking about are the net import reliance statistics that

we – that we produce and that we are now building in directly to this model.

Production country concentration – so the kind of data I showed you

for tantalum for the shift from Australia and Brazil to central Africa.

And then growth in world production, price volatility, and then the

world governance indicators that we get from World Bank.

But all these ones in green we actually report every year.

We don't – we don't collect all of that information ourselves.

Price volatility, for example, we subscribe to publications that track price.

We consolidate that data. We report averages on an annual basis.

But we do publish that information all in one place.

It's in the public domain, so it's available and transparent for people.

And we've used it to good effect, I think, for our modeling efforts.

So with that, I will stop. I think I'm about on time.

It's time for questions, I think. So thank you.

[ Applause ]

- Thanks, Steve. I'm going to ask people to

please go to the microphones. I think you all know the drill.

- I have two questions.

- Your mic's not on. - Do I have to do that?

- It should be on. Mitch?

Can you check to turn on the floor mics?

I have this one. And it's on.

- Pardon the frog in my throat here. - Okay. First, China.

Do they just have more from a geological perspective of lots of these minerals

than other places? Or are they doing a better job of taking advantage of it?

And number two – I'll ask them both first.

The second one is, Afghanistan, there was a big news story a

couple of years ago about how they were going to be –

had this major concentration and, you know, ability to produce.

They might be – not have the stability to do it, but how does that – is that –

is there any update on that, and does that factor into

these commodities that you're talking about?

- Okay, so first China. China is, for most – for many of the

materials we're interested in, is the largest producer as well as consumer.

China is obviously well-endowed with mineral resources.

But so is the United States. All right, I mean China has chosen

to develop their mineral resources. In many cases, they're doing it in

an unsustainable way, in our view. And I think even their government

is recognizing this and recognizing that it cannot continue.

So you see things, for example, like iron ore.

The grade of iron ore in China is, like, you know, 20%.

You can dig iron ore in the ground in Brazil, it's, you know, greater than 60.

And in Australia as well. So they are increasingly purchasing

their iron ore from Australia and Brazil.

So they're not going to continue mine iron ore that's 20% grade.

It just doesn't make sense. And it's true for a lot of other commodities.

But they have a very rich mineral endowment.

They have chosen to exploit that. The United States has a very

rich mineral endowment. And we have, for the last 60 years,

moved away from exploiting our domestic mineral resources.

And it's resulted in very large import dependence.

It doesn't mean that we can't reverse it, but I –

as I said before, it will not happen quickly.

Afghanistan has a lot of potential, again, and is back in the news.

And in fact, we've been asked recently by USAID to revisit Afghanistan.

A lot of the work was done there that was sponsored

by the Department of Defense some years ago now.

In recognition of the fact that, you know, if there's ever going to be

an end to the war in Afghanistan, they need to have some kind of economy.

So we will be revisiting Afghanistan. They have a lot of potential.

They have a lot of issues, obviously.

It's not enough to just have mineral resources.

You've got to be able to mine them and get them out of there,

and the infrastructure is very bad. Security situation is very bad.

But presumably, that's not going to continue forever.

Although, if you go back to Alexander the Great, you could

probably argue that it's been that way for quite a long time in Afghanistan.

But we will be revisiting that and

hopefully getting some funding from USAID to do that.

- Maybe a somewhat similar question with it.

So we saw, over the last 60 years, that the trend was for mineral supply

to move from Canada/Mexico to the Soviet Union and China.

Are there any more general trends that have driven that besides just

the fact that China's aggressively developing their resources?

- Well, I think, you know, for the U.S., I mean, we have, by far,

still the world's largest economy, or at least in nominal GDP.

And so our resource needs are large. And since – particularly since the '70s,

and I – you know, I don't want to make a political statement here,

but when we implemented environmental laws in the United States,

and the rest of the world, you know, didn't necessarily follow along, it kind of

had the natural effect of pushing a lot of that activity to other countries.

And so that clearly – and I can't quantify that,

but clearly, since the '70s, there's been an acceleration

in our dependence on mineral materials mined

from other countries that is clearly part of this – part of this issue.

I mean, I think that, from my perspective, that when we say

we're not going to mine materials domestically that we need,

we're going to let some other country do that.

And maybe some other country that doesn't have the same standards

we do and not doing it in a sustainable way, that we are being

a little bit hypocritical, to be honest. We're going to – we don't want

to get our hands dirty because, you know, people don't like mining.

So we're going to have it done over here.

I think we're kidding ourselves that we're doing something good from the –

from the bigger picture. I don't think we are, really.

I think you could argue that it would be better to do mining

in jurisdictions where they have the rule of law, where they have

environmental regulations, where the mining is being done sustainability.

And Canada and Australia, in large measure, are doing that.

So it can be done. It could be done here too. We've chosen not to.

- This may be a loaded question, but … - Okay.

- A couple years ago, when I was doing research on my book,

I spoke with Dudley Kingsnorth. - Mm-hmm.

- And he said, at that time, the estimate for the black market

was anywhere from 25 to 60%. Since you obviously incorporate

economic data and rely on other services for some pricing, how do you

factor the black market in … - We do not.

- You don't at all? [laughter]

- We report – the rare earth numbers we report from China are the official

numbers. We – you know, we know that there's illegal mining in China.

Dudley, I think his most recent estimate is 40% of heavy rare earth

production is probably illegal. It might be more than that.

But we can't, as a government agency, say that 40% of, you know, heavy

rare earth mining in China is illegal. We just are not going to say that.

In much the same way that, you know, people have asked me

why we have a number for reserves in Canada for copper that is X.

And the answer is, because that's the Canadian government's estimate

of what the reserves are for copper in Canada.

We're not going to publish something that is contrary to, you know,

the government – official government report from another government.

Other people will report, you know, other things, and they're free to do that.

But, you know, we are a government agency, and we have to be cognizant

of our role and our responsibility. So we're not going to – we're not

going to comment on, you know, how much of rare earth production

in China might be illegal in our official publications.

I mean, everybody knows that it's going on. It's been widely reported,

and it's any number of publications, but not in – not in ours.

- I think that's essentially my question in – how comfortable are you

with the transparency and reliability of the data, both from countries and

for corporations that clearly have strategic perspectives and

might not want to, you know, show their hand for various reasons?

And yet, we're – anyway, so … - Yep.

- … how does that enter in your … - Well, that's a very – that's a

very good question, and it's a very important aspect of what we do.

I mean, the data we collect domestically

is from direct canvassing of U.S. producers.

All right, they don't have to comply. They don't have to reply to our inquiries.

But they do, typically, if it adds value for them.

It's very different for information we source from other countries.

And so we rely on a wide variety of different kinds of information.

You know, our connections with other government agencies,

people from the U.S. that are on the ground in other countries,

such as embassy staff, private – the private sector.

So we try to collect information from as many different sources as we can.

In many ways, that part of our mission is akin to intelligence gathering,

where you have lots of different inputs, and you have to sort of decide,

based on the expertise of our specialists, what our best estimate of those

quantities are for countries where the information is

less than transparent, which is for many of them.

Another thing that we do often is send people on the ground.

Some countries, you know, I'm not going to send my people

to because the security situation is not – does not allow it.

But we had, for example, one of our Africa specialists was in the DRC and in

Rwanda within the past couple years to talk to traders and other people that

are involved with the material flow of tantalum in particular out of the DRC.

So we rely on a whole range of different sources.

And we do the best job we can to evaluate that information

and make our best estimate.

We also rely heavily on trade data, which are, because they're commercial,

more readily available. That has its limitations too.

Tantalum, for example, is lumped in with niobium often because they're often

associated in the – in the mined product that people will get those materials from.

But that's another good source of information

that is more transparent, right? Trade flows – even if a country is

not very good at recording their trade flows out, if it comes into the U.S.,

we're pretty good at recording it, as are most people.

So the major trade flows are – I think are reasonably well-defined

and are a good source of information for us.

- Not to drag you into politics. I've been reading a great deal

for two weeks or so about uranium situation and the

Uranium One deal as though this were some national security

emergency, though I certainly can't see why.

And I wonder if you could speak a bit about the uranium supply situation.

- Yeah, we don't actually cover uranium. So I'm going to dodge

the political question. [laughter]

We cover non-fuel minerals. There are people in USGS that work on uranium.

And so I don't really know a lot about the domestic supply situation

for uranium. I think most of what we're getting for domestic consumption

is actually coming from Canada, which is not particularly of concern,

I don't think, assuming that we, you know, maintain civil relations

with our neighbor to the north. [laughter]

So I really can't comment on, you know, domestic supply for uranium.

We do not perceive that as a big risk, though, but others may.

Yes?

- I noticed that you talk a lot about things not being mined

in the United States. - Mm-hmm.

- But there are – minerals are not evenly distributed.

So how many of these things that we import are not available in the United

States in significant quantities at all? - Probably very few, to be honest.

And, to some extent, we don't really know.

This is why the Senate has asked us to do this report and about what we

do know and identify things that we don't know about

that we need to study – to do resource assessments for.

But there's, I'm almost certain, lots of mineral potential in the U.S.

that we still don't know about, particularly in Alaska.

And it's a matter of doing resource assessments for those materials.

The other aspect of that is that a lot of the materials that we're

most concerned about are produced almost entirely as byproducts.

And so they would be potential byproducts for major commodities,

such as copper or nickel. We really haven't done a

very good job of evaluating what the potential are for those kinds of materials.

Also, there are significant byproduct mineral concentrations with precious

metals. And there is a lot of focus on precious and base commodity metals.

So that's part of – I think an important part of what we need to do in the

next 10 years or so is to really understand better what the potential is

for domestic mining and identify the most interesting areas

that the private sector can then go and develop.

Yes?

- Do you see any evidence in the current Congress or in the administration

that would give you some evidence that they would – that the United States

will eventually have to reduce their need for imports and have more

internal building of this commodities? - Okay, so I'm going to be careful not to

make any political statements here. [laughter]

- I know. - I think certainly, I can say that

there is a heightened interest in the new administration in natural resource issues.

They particularly are focused on energy, as you're probably aware,

and energy on federal lands, but also, I think, minerals as well.

I think certainly, I think the secretary of the interior understands

that issue pretty clearly and thinks that it's important.

And so – and there certainly are people in Congress – Senator Murkowski

chief among them, but also people in the House who have, for years now,

been trying to prod our government in the direction of doing something to

make it a little bit easier to develop mineral resources in the United States.

Senator Murkowski has been introducing a legislation for several years now,

and she has a bill again in this – in this Congress that actually,

I think if it were brought up, could pass.

Because it has pretty broad support – bipartisan support.

It's got a lot of things in it that a lot of people agree on.

And it involves both energy and minerals.

So there's some chance that – I think, that we are going to

start to make progress on this. I think it's clear to many people,

myself included, that, you know, that it's time for this to happen.

Whether it will or not, we'll have to see. But because it does take so long to,

you know, identify and develop and put a mine into production, it's not like,

you know, we've got a lot of time to waste.

So it's either now or we're not going to get –

we're not going to get there. Yes? Next?

- It seems like you've done a lot of sophisticated –

you've done a lot of sophisticated modeling on the supply side.

And you mentioned, in some cases, the demand side.

But do you have a similar depth of information and modeling

on the demand side for all of these materials?

- No, not really. And there are two schools of thought on that.

We'd like to do more on the demand side, but the demand side

is a lot harder to measure. We do report consumption every year.

And we report, you know, increases in consumption.

But demand, particularly at a granular level, is difficult.

And it's very difficult to forecast.

And if I could predict the demand for mineral commodities, I would be

a mineral commodities trader, and … [laughter]

I'd be, you know, making a gazillion dollars.

But you can – you can – you can identify – and I've given talks

on this before. Because people always want us to predict the future.

And I always say that I'm not very good at it.

But you can look at broad sectors of the economy and say, all right,

what do we really – what do we know we're going to need?

Well, we need energy, and we're dependent on technology.

We need to eat, right, so fertilizer minerals for agriculture.

For transportation, we – you know, electric cars are coming, so we know,

based on current technology, that demand for lithium and cobalt

and manganese and graphite are going to increase

pretty dramatically in the next few years.

So you can – you can look at those big trends and say, you know,

these are the kinds of materials we know we're going to need.

You look at people's projections about, you know, what fraction of the

world's automobile fleet is likely to be electric cars by 2040

and get some idea about that. But it's more difficult,

and you're more likely to be wrong in making those

kinds of predictions. But we do the best we can.

- So my question is a little bit of a follow-up to something

that you briefly just talked about, which is that there's a lot of uncertainty

about the potential to mine these things in the U.S.

And recently, I've been worked with the USGS maps, spanning from, like,

the '30s until the '70s that are the oil and minerals for fuel resources maps.

- Uh-huh. - And clearly that was an extensive

effort and push to get all of those made. So I guess I'm just sort of curious what

it would take to do something similar for some of these non-fuel resources.

- Yeah. It's a very good question. And, you know, the new associate

director for energy and minerals at USGS has been pushing

exactly the kind of plan I think that you're talking about.

It's called 3DEP. And it would complete geologic

mapping of the United States, which I think we've mapped –

at the scale that would be necessary to guide the private sector

in developing their own deposits – like, 17 or 20% of the U.S.

If we look at countries like Australia and Canada, they have

a much more extensive coverage. And because of that, it's much easier

for companies to make decisions about developing mines in those countries.

But that would be coupled with geophysical surveys

that would give us the third dimension, in addition to the geology,

over large sections of the U.S., particularly the western U.S.

So there's – you know, there's an initiative that's, you know,

floating around downtown somewhere that would do exactly that.

I think it would be, like, a five- or 10-year effort, at least initially.

Probably would take longer than that.

But, you know, certainly that is something that we can and should do.

And that's not just, you know, USGS saying that.

I mean, Congress has heard that from industry.

There's been testimony on the Hill about that very subject.

And CEOs have told them that we just don't have the baseline information

that Australia and Canada have, for example – countries that have

very similar, you know, legal and environmental jurisdictions to us.

And they are successfully and sustainability developing

their mineral resources.

There are a number of other things that we should do that directly involve,

you know, support for USGS. But, you know, I'm not supposed to

ask for money, so somebody else will have to ask for it.

But that is one initiative that has been floated downtown and is getting some

traction. Hopefully we will see that come to fruition, maybe in fiscal '19.

- Platinum is extremely important for many, many reasons.

And the U.S. has virtually none.

And I'm wondering about your – what comments you might make about …

- Platinum? - Platinum.

- Yeah, okay. Actually, we do have platinum.

The Stillwater complex is a pretty significant source of platinum-group

elements, and it was just acquired by a South African company – Sibanye.

But it is considered by most analysts as a critical mineral.

In part because concentration of production is quite high

in South Africa and Russia. And, you know, South Africa is clearly –

had a lot of issues with governance in the past few years.

Their government is viewed, I think, as doing things that are not very

supportive of the mining industry, and they've been heavily criticized for that.

So it is a material that we are concerned about.

We do have some domestic capacity there, so it's probably not

at the top of the list, but it's clearly important

going forward and something we're going to have to keep tracking.

- We are a very minor producer of it, I believe.

- Yeah. But we at least have some. And we have mining operations –

viable mining operations. Which you can't say for

some of the other materials we're talking about. Yes?

- I'm not quite an audience plant for this, but I'm getting the impression that

you are very interested in domestic production, or at least examining it

and wondering how we can approach it more responsibly, both socially and

economically, and environmentally. You keep mentioning

Australia as a leader in this. Can you talk some about what it

would take to develop mineral resources in a responsible way, which would

avoid the not-in-my-backyard sort of push to make it external?

- Yeah, I'm not sure I can answer that or solve that one.

Part of it is education. People, I think – you know,

we've sort of evolved to a society that is, in many ways, detached from the

physical requirements that support our standard of living – minerals, energy.

I mean, we just don't – you know, people think that gasoline

comes from a pump and that, you know, the smartphone comes from,

you know, Amazon.com or something.

So part of it's education. And that's – you know, we do a lot of that in USGS.

I speak regularly to groups about, you know, our raw material needs

and how that relates to people's standard of living.

That – even that is probably not going to convince some people

because people don't want to give up things, right?

And that really is what – you know, people who tell me that they don't want

to mine, what they are saying to me is that, I don't want to mine here.

And so my immediate question then is, well, what do you want to give up

in exchange for not mining, you know, in our country, or not mining at all?

You know, you want to give up your smartphone?

You want to give up your car? What is it that you want to give up?

You can't – you can't have all of these things without mining. And by the way,

we can't have, for example, renewable energy without a lot of mining.

I worked in the mining industry for a long time.

I know mining can be done sustainably.

You know, the mining industry today – the modern mining industry is

not the mining industry of 50 years ago, which is what a lot of people look at

and say – you know, we've got all these legacy issues,

and so we don't want to – we don't want to do this mining.

But there's really no escaping the fact that much of the extractive industries

are, you know, very disruptive. I mean, you have to dig, right?

You have to dig holes, and then you have to –

you know, you produce materials that you can't use.

But it can be done responsibly and sustainably,

and companies are doing it. And increasingly, they are required to do

it that way, and you have to – you know, you can't just, you know, mine and then

walk away from it and leave the legacy costs for the – for the society to absorb.

So, you know, I think we just have to continue to try to make the case

to people that, you know, if you want to have the things that

you value and that support your standard of living, then we have to have mining.

Whether it's done here or somewhere else, it has to be done.

And there's really no escaping that.

And from my perspective, it's better to do it in a sustainable way than it is

to push it off somewhere else where it's not going to be done responsibly.

Because, you know, the people there will suffer

because of that, and globally it's a – it's a net negative.

But I don't have any easy answers. Because it's the kind of thing that –

you know, that some people are just never going to accept.

I try not to be – sort of come off as, you know, the Mr. Miner,

Mr. Industry Miner guy. Because, you know, USGS is a fact-based

scientific organization, and we are trying to present the facts as best we can.

But it is a fact that we depend on these materials, and increasingly,

we're not producing them ourselves.

So if that's going to continue, then I think we're going to have problems.

- Steve, thanks. Very interesting talk, and Diane

allowed me to make one more question. Your last response led me to wonder,

are all these things single-use commodities?

We're not talking about reusing our lithium, reusing these

various commodities? They go into our landfill,

and then they're no longer available or the source of …

- I think most things, in principle, can be recycled. Many are not these days.

I mean, we've just done a study of tantalum to look at, you know,

the global lifecycle of tantalum flow. And very little of what's been

mined is actually being recovered. So we've got a lot more

work to do on recycling. And again, you know, this is an area

where the U.S. is well behind our allies. I've been to facilities in Japan where

they are developing technology to extract trace metals from

electronic scrap, for example. People have been extracting the precious

metals for a while from those materials, but the trace metals that we're

talking about – tantalum and other things –

we don't have the technologies for most of those.

Things like lithium, you know, recycling of lead acid batteries is ubiquitous.

I mean, they're almost all recycled. There's at least one company

in California that is recycling lithium-ion batteries, and I expect that,

with widespread adoption of electric cars and lithium-ion batteries that

those materials are going to get recycled. I mean, those are perfect unit

uses of materials that can readily be segregated in a waste stream

and the materials recovered.

But there are commodities that the U.S. recovers significant portions of.

I mean, for example, domestically, we get about

half of our tungsten from recycling.

So some things are easier and more readily recycled than others.

And that's certainly part of the answer.

With the anticipated growth that we expect in global consumption,

it's not going to be enough. We're still going to have to mine.

But it certainly can contribute to the global balance, and in a very positive

way. So we've got to work on the technologies to recover those things.

And that, in part, means, you know, learning how to design things in a

way that allows them to be readily segregated at the end of life.

If it's just too convenient to throw it away,

then that's what's going to happen. But if you make it easier to recover those

materials, then it'll be economic to recover them, and people will do it.

- Do you know whether U.S. government invests in pilot-light

projects for mineral resources?

- For which projects?

- Mineral resources. Mineral resources.

I'm thinking specifically – I'm remembering the –

when China cut off the rare earth supply, and it took us some time to restart the

Mountain Pass mine or other sources. - Yeah. Mm-hmm.

- Do you know that there – are there projects to keep open in a mothball state

or a pilot-light state some … - From the government's …

- Yes. The government. - Yeah. None that I'm aware of.

Though there is a – there is a provision in procurement policy for the

Department of Defense called Title III that would allow

the Department of Defense to get involved in projects that –

for materials they viewed as particularly critical.

As far as I know, they've only used it once. That was for beryllium.

They basically made an arrangement with Materion – a U.S. company

that mines beryllium in Utah – to build a facility in Ohio that

makes high-purity beryllium metal and beryllium compounds,

which are essential for defense applications.

So the Department of Defense used this Title III provision to

basically ensure Materion that they would make a return on their

investment is what basically – if you build this facility,

we will take a certain amount of this material at market prices.

So there's a mechanism there. It's been very – it has not been used

extensively at all for materials. They may be using it in other areas.

It's a procurement policy.

But I know they are considering doing that for other materials.

And I think it is one way that government can take

a more proactive role. And, you know, we are certainly,

you know, engaged with our U.S. government agency partners to help

them understand what the most critical materials are and the forms of those

and are happy to, you know, advise them on that.

It's really part of our role is to – is to give the other agencies the

facts they need to make those kinds of decisions.

Yes?

- Could you – could you say more about the tungsten recycling?

I have no idea where it's used, it would …

- Yeah. So tungsten – the principal use in the U.S. is in tungsten carbide used in,

like, drill bits for hydrocarbon drilling and other kinds of drilling.

So there's a kind of closed loop there. You know, so when these wear down,

the materials get recycled back to the manufacturer and recovered

and put into new tungsten carbide for – mostly, I think, the major application

is for drilling applications. - Thank you.

- Going once? Going twice?

[laughter]

Well, Steve, thank you so much. That was a delightful talk.

And you all have to really thank him.

He flew out from our Virginia office to give this talk.

[ Applause ]

- My pleasure. Thank you for all the great questions. Appreciate that.

- And thank you all for coming here. Hope to see you November 30th.

[ Silence ]

For more infomation >> Spirits believed to be lingering in Lewiston Public Library - Duration: 2:27.

For more infomation >> Spirits believed to be lingering in Lewiston Public Library - Duration: 2:27.

For more infomation >> Ginther, city leaders update public on crime-fighting efforts after city's 111th homicide in 2017 - Duration: 1:55.

For more infomation >> Ginther, city leaders update public on crime-fighting efforts after city's 111th homicide in 2017 - Duration: 1:55.

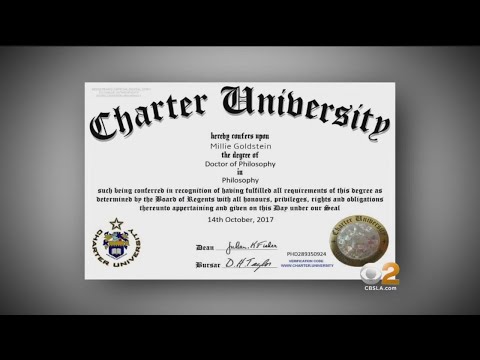

For more infomation >> Are Public Emplyees Getting Degrees From Diploma Mills To Further Their Career? - Duration: 5:00.

For more infomation >> Are Public Emplyees Getting Degrees From Diploma Mills To Further Their Career? - Duration: 5:00.  For more infomation >> Public Works employee shot to death on lawnmower - Duration: 0:44.

For more infomation >> Public Works employee shot to death on lawnmower - Duration: 0:44.  For more infomation >> Public works employee killed - Duration: 1:18.

For more infomation >> Public works employee killed - Duration: 1:18.

For more infomation >> Public Fool - Duration: 21:14.

For more infomation >> Public Fool - Duration: 21:14.

For more infomation >> Public Royalty : Meghan Markle : quelle robe pour son mariage avec le prince Harry ? - Duration: 2:21.

For more infomation >> Public Royalty : Meghan Markle : quelle robe pour son mariage avec le prince Harry ? - Duration: 2:21.

For more infomation >> FBI: Tips from public help prevent terror attacks - Duration: 1:52.

For more infomation >> FBI: Tips from public help prevent terror attacks - Duration: 1:52.

For more infomation >> Restoration at Sabine Hill in Elizabethton complete, open to public for tours - Duration: 2:40.

For more infomation >> Restoration at Sabine Hill in Elizabethton complete, open to public for tours - Duration: 2:40.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét