MITCHELL BERGER: Our next speaker is Gerard Scheitlin from Orion Health. Mr. Scheitlin?

GERARD SCHEITLIN, ORION HEALTH: Good morning, I'm Gerard Scheitlin from Orion Health.

I'm the chief risk officer and vice-president of security risk and assurance.

Orion Health is a population health and precision IT medicine provider,

so we're in Health IT (HIT). We're a technology company that

provides the solutions that a lot of you have used to look at the

records to manage what you're managing.

I appreciate what SAMHSA is doing to protect the privacy and rights of

individuals. I understand the need for consent.

But when you look at what is going on in the electronic healthcare information exchange,

when you see what the ONC (Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology) is doing with the

Trusted Exchange Framework and the Common Agreement – or TEFCA –

there is a discussion about moving this nationwide,

about having consent flow nationwide.

All right. When you do this, and you take the consent and you put it into that manner,

it's becoming more and more difficult to manage. It's becoming more and more difficult to manage electronically,

not because we can't say, "Yes, this person's consented,"

"No, this person has not consented," but because we can't manage the

permutations, combinations, and the different rules that are in there.

It's going to become programmatically a major challenge.

So, unless we align and simplify, unless we align and come

down and align with HIPAA and align with consent

across it – because it's no longer managing consent in a

specific facility, in a specific organization. It's managing it across states.

It's managing it across multiple facilities across multiple states.

States have different laws.

States have different rules. Opt-in states say you're automatically consented in.

Opt-out states say you have to consent in if you want your information exchanged. It's becoming extremely difficult to measure that.

And then when you toss in another layer, the sensitivity of data,

and if you toss in different layers of sensitivity of data,

even when you talk across drug abuse, sexual health, pregnancies,

other things, it becomes a very difficult task for any HIT provider.

So, I've listened to some of the comments in here, and I've heard

people talk about the health information exchange,

that it's not providing the information. The reason is, is the

complexity of it doesn't allow the technology organization

underneath to provide that information and put those rules in place.

Because of the complexity level, it becomes too much of a

challenge to even attack programmatically. So, I strongly urge

SAMHSA to work with CMS and ONC to understand

what they're doing with TEFCA, to understand what they're

doing with these laws and consents and simplify it across the nation. Thank you.

MITCHELL BERGER: Okay, great.

We're ready to start taking questions over the phone. Can we have our first speaker, please?

OPERATOR: Certainly. Thank you. Our first comment comes from Christine Kerno.

CHRISTINE KERNO, ADDICTION MEDICINE CLINIC: My name is Christine Kerno. I am the supervisor of Addiction Medicine Clinic in Hennepin County

Medical Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. I actually have a couple of questions.

We are moving cautiously to implement the changes in CFR 42 Part 2.

And so, my questions are, specifically, what is the wording for

releases of information so that we can share information to provide integrated care?

We're an opioid treatment program located in a very large public hospital,

and we're very cautious with this, and we have firewalls even

within our own hospital so that medical providers cannot see

any of our notes in our opioid treatment program (OTP) or any of our work with patients.

So, my questions are, what exactly is the wording on a

release of information (ROI) we can use now? Is the ROI now

going to be something we can use for people for integrated care

with all providers we come in contact with over, say, a year's

period of time inside the hospital, outside the hospital?

And also, do we have to add to the list every time we contact or

speak with the same outside psychiatrist or case manager?

Do we need to immediately put it on the list on the ROI?

That's my second question. And is the current change

allowing us to think about taking down our firewalls so that

medical providers in the hospital, when they see our patients in the

ED or on a medicine floor, kind of can immediately see the current

treatment situation with the patient?

So, are we already at this time given permission, or is it legal, to now

take down those firewalls and have other providers in the hospital aware of their

OTP treatment to provide a better integrated care experience? Thank you.

MITCHELL BERGER: Thank you very much, and you're more than welcome.

As we said at the introduction, we're not really taking questions and

answers today, but you're more than welcome to submit those questions to us by

email, and we have your questions from the transcript, so we can note

those as we look at the outcome of this meeting. We're ready for our second

person over the phone, and for the people over the phone, please state your

name and title and organization. Thank you.

OPERATOR: Our next question or comment comes from Tom Anderson.

TOM ANDERSON, FRONTIER BEHAVIORAL HEALTH: Yeah, this is Tom Anderson. I'm the HIPAA Privacy Officer with

Frontier Behavioral Health in Spokane, Washington. And our question relates to the ongoing issue

under 42 CFR Part 2 where, when we share information, a client

signs an ROI to authorize us to share information with the physical

healthcare provider. We're still required, and I don't think the

new rules change, for us to include the notice prohibiting

redisclosure of that information by the recipient, which is the

physical healthcare provider, to another healthcare

provider that's treating that patient.

And the physical healthcare provider is not a Part 2 provider as we are,

and it really prohibits any kind of integrated care, because our

information that we provide is integrated information.

We don't have specific separate information around substance

use disorder treatment, because so many of our patients that we treat

in our behavioral health organization have substance use

disorder issues as part of the diagnosis that we're addressing.

So, it's an integrated plan, and so, all of our charts, before we can

release information, we require folks to sign a Part 2 compliant ROI.

But the physical healthcare provider is not familiar with that, and it's really

not set up very well for them to be able to share to get a

separate release before they can share that information with another specialist,

and their ROIs do not meet the 42 CFR Part 2 restriction prohibiting redisclosure.

So, while we appreciate the fact that the changes

have addressed the operations and payment sections

related to HIPAA, the treatment sections, it really still is not

viable to really call us being able to provide integrated

care when the treatment sections under Part 2 still prohibit

that redisclosure. So, the redisclosure issue is really the main

concern that we have that needs to be addressed,

or else people that have substance use disorder issues really

are not going to get integrated care, and it's really going to be an

ongoing problem for any kind of integrated health system. Thank you.

MITCHELL BERGER: Thank you.

OPERATOR: Our next question or comment comes from Karolina Austin.

KAROLINA AUSTIN, OPERATION PAR: Good morning.

My name is Karolina Austin. I am speaking on behalf of Operation PAR in Tampa, Florida.

We are the largest not-for-profit provider of addiction treatment services for adolescents and adults in the

Tampa Bay area of Florida. Our organizational goal is to provide high-quality care and service to the

communities within the areas that we serve.

As a provider of substance abuse treatment services, PAR is intimately familiar with the

difficulties surrounding compliance with the federal confidentiality regulations.

We ask that the following restrictions align more closely with HIPAA.

Authorization restrictions: Under Section 2.31, "Entities without a

treatment provider relationship," the new regulation

requires the name of the individual to whom the disclosure is being made.

We at Operation PAR have many clients who are involved in

child custody cases, as well as cases within the drug courts.

Many of our clients do not know the names of the caseworker

assigned to them until we receive a request for records.

Oftentimes, the client's caseworker changes, or the clients

can have multiple individuals assisting them with their case or investigations.

This new regulation provides challenges and barriers for our

agency and clients to release records in a timely manner.

Clients oftentimes call us stating they have a new caseworker

and need records sent to them immediately due to a pending

court case that they are waiting on. We are unable to assist the clients due to not having proper written consent.

Many of our clients do not have transportation to come and complete new authorization forms, or access to a computer.

These requests are oftentimes sensitive with little to no time to disclose records.

Due to the definition, the Department of Children and Families and drug courts do not fall under a treatment provider relationship.

This limits the consents and presents challenges when we are assisting clients to regain child custody of their children or

comply with the courts.

We would like to request that changes be made in the regulation under 2.31

to allow the release of records to an entity name and not to the name of an

individual for the following agencies: The Department of Children and Families,

drug courts, juvenile justice system, and the criminal justice system for probation and parole. This will allow our

agency to more effectively assist clients with their open court cases.

Arrest warrants, subpoenas, and court orders under Section 2.61:

This regulation presents challenges for Part 2 programs.

Part 2 programs are unable to consent due to clients no longer

being in our programs or obtain consent, or the client is unwilling to sign one.

This forces Part 2 programs to obtain an attorney to submit a response to the courts.

More oftentimes than not, the judge submits a 42 CFR Part 2-compliant order releasing the records.

For Part 2 organizations, this uses unnecessary time, costs, and

provides bad business relationship with their requesting courts.

This also sets a bad precedence to our clients that they can delay their court cases by

refusing to sign a consent for the release of records.

Risk of our reputation with the courts, and the courts offering to refer individuals to our services for non-criminal offenses are at risk.

The state attorney's offices can take the refusal to release records on a subpoena or a delay to release records as a

sign of the Part 2 program are trying to hide information and can have a negative consequence against our clients.

We ask that the regulation fall more closely in line with HIPAA,

which would allow the disclosure of information without consent if the

order is signed by a judge. This would prevent delays,

noncompliance, and provide a better rapport with our courts and our affiliates.

We would like the Part 2 regulations to become less restrictive.

And in conclusion, on behalf of Operation PAR, I would like to

thank you for the opportunity to express our concerns over the 42 CFR Part 2 regulations.

We respectfully request SAMHSA's urgency in addressing these

identified issues under Part 2 in order to ensure timely and

effective care coordination and improved healthcare outcomes for the benefit of our patients in Florida and nationally. Thank you.

MITCHELL BERGER: Thank you very much.

OPERATOR: Our next question or comment comes from Pat Reher.

PAT REHER, HARTFORD HEALTHCARE: Thank you.

This is Pat Reher from Connecticut, former commissioner of the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services,

and currently serving as president of the behavioral health network for Hartford Healthcare,

the largest behavioral health network in the state of Connecticut.

I agree with most of what has been previously said,

that unfortunately the current status of the CFR 42

leave us in the position of not being able to communicate with providers after somebody has

left or completed a treatment program, which leaves them at high risk, and one of the issues that

I think this highlights in the behavioral health system is, again, the issue of discrimination

against people who are seeking treatment and who need continuing care.

In most other medical illnesses – and we know that this is a

brain disease and a chronic, relapsing illness – we would not

hesitate to communicate to a primary care physician or

other treaters about the treatment that the individual has experienced,

either in a hospital or in a detox center, or even an ambulatory detox center,

and as somebody stated previously, we see people in an active

detox program who may still be in a contemplative state and refuse to sign an ROI,

and it puts them at high risk of going back to a primary care provider (PCP)

or another medical provider, getting a prescription for some sort of opioid,

and then overdosing because they've used the same amount as they

used prior to admission. So, we feel that the risk is, frankly, high enough so that it can increase the risk of overdose

In the state of Connecticut last year, we had 247 individuals that

died in automobile accidents, and 916 that died from opioid overdoses.

Thus, the scope of this crisis is significant enough so that

I think that we really have to evaluate the federal laws that, in some ways,

keep us from communicating adequately about the individuals

that we serve that is so different from the way we

communicate about any other medical condition. Thank you.

MITCHELL BERGER: Thank you.

OPERATOR: Our next question or comment comes from Mark Parrino.

MARK PARRINO, AATOD: I'm Mark Parrino, and I serve as the president of AATOD,

which is the American Associations of the Treatment of Opioid Dependence.

We understand the complexity of what SAMHSA is trying to engage in,

and we appreciate it. Literally, we support, as an organization of opioid treatment programs –

and there are 1,500 of them in 49 states –

the idea of integrating and coordinating care for the patients.

We have some comments.

The question for us becomes, Have attitudes shifted so

markedly about patients receiving medication to treat opioid disorder since the original

confidentiality regulations went into force, as has been said, during the Nixon administration?

The next question becomes, "How are patients treated once the information is disclosed?"

Now, I've heard the arguments in favor of it, and I understand that SAMHSA is trying to align where it can 42 CFR Part 2 with HIPAA.

The issues, however, are once information is disclosed about their

being on either methadone or even buprenorphine,

patients don't get access to life insurance or disability insurance.

And there's a question about how the PDMPs handle it.

If OTPs are expected to disclose confidential patient information to PDMPs,

there would have to be strict enforcement that the PDMP would only

share such information with healthcare providers,

and there would have to be clear understanding that enforcement authorities could not get this.

I give you the evidence of Oklahoma, where the PDMP is directed by the State Enforcement Authority,

and they take the view that sharing the information of OTPs

into a PDMP should also serve to cross reference any outstanding warrants.

That's not the point of a PDMP.

Additionally, at the present time in Michigan, it's routine to have patrol cars parked near an OTP,

and then, as patients leave treatment, follow them and then pull them over subject to potential DUI.

The issue with Virginia is also clear in that if a mining

company learns that a patient is enrolled in an OTP and getting methadone,

they can't continue to work, and then the OTP and patient must convert to buprenorphine.

For some reason, buprenorphine doesn't carry the same stigma with

coal mining companies in Virginia as does methadone.

So, rather than give you more stories, I appreciate the fact,

and we at AATOD appreciate the fact, that you want to do all that you

can to integrate healthcare services. And I understand the

issue of electronic systems and electronic healthcare records,

but still and ultimately, this comes down to how best to protect the

interests of the patient, especially at a time when the patient is

deciding whether he or she should enter treatment and then remain in treatment.

This is especially true for pregnant patients who are wondering,

if they enter treatment, will Child Protective Services take the child?

So, as you go through this debate, and I appreciate the

sensitivity that SAMHSA has demonstrated in this balancing act,

these are all very important points to keep in mind, especially in the evolution of attitudes towards people who seek treatment.

I can assure you, the attitudes in many corners are not good, including the medical community.

Thanks for the comments, and I appreciate the difficulty of what you are trying to do at SAMHSA.

MITCHELL BERGER: Thank you. We'll go back to in person, and my colleagues.

MODERATOR (Suzette Brann): Good morning, everyone. Can we have Deborah Reid from the Legal Action Center?

DEBORAH REID, LEGAL ACTION CENTER: Good morning. I'm Deborah Reid, senior health policy attorney for the Legal Action Center.

The Legal Action Center is a nonprofit law and policy organization that

fights discrimination against people with histories of addiction, HIV and AIDS,

or criminal records and advocates for sound public policies in these areas.

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on Part 2 and its effect on patient care,

health outcomes, and patient privacy.

The Legal Action Center firmly believes that it is important to maintain

Part 2's core protections and heighten privacy standards for

substance use disorder treatment records, since adopting a HIPAA standard

would not sufficiently protect people seeking or receiving substance use disorder treatment.

We support patients' rights to participate in models of

integrated care and the electronic health record systems while

maintaining the right to control the disclosures of their records.

Part 2 improves health outcomes in patient care by encouraging people

to enter and stay in treatment without the fear that their

treatment information will be disclosed.

This is the original intent of the regulation.

Without Part 2's protection, people will be discouraged from

seeking treatment for fear that their treatment information will be

used against them in criminal proceedings or jeopardize their jobs, housing, or child custody.

Considering the current opioid epidemic, these protections are just as

important today as they were 40 years ago when Congress

passed the original legislation authorizing the Part 2 regulations.

Moreover, Part 2 gives patients the tools to manage

disclosures of their substance use disorder treatment information,

because unfortunately stigma and discrimination continue to exist,

even in today's healthcare field. Part 2 protects patients from discrimination,

which leads to better patient care and health outcomes.

Part 2 supports patient privacy and strikes an appropriate balance

between maintaining patients' confidentiality and encouraging integration of care.

Because the technology already exists to segment data,

the appropriate next step should be to bring integrated care and

health information systems into compliance with Part 2.

We also urge SAMHSA to issue the subregulatory guidance on the

topics it identifies in the January 2017 final rule. SAMHSA has made

major changes to Part 2 that have been in effect for less than a year.

In our experience, the programs, vendors, and other stakeholders

are still becoming familiar with these changes. For this reason, we are

not recommending any further regulatory amendments at this time.

Instead, we encourage SAMHSA to issue subregulatory guidance.

Further recommendations are set forth in our written comments,

which will be submitted for the record. We appreciate SAMHSA's ongoing commitment to protect and

promote the health of people who are living with substance use disorders. Thank you.

MODERATOR (Suzette Brann): Thank you. Al Guida, from Guide Consulting Services?

AL GUIDA, GUIDE CONSULTING SERVICES: Good morning, and Dr. Johnson, thank you for inviting us here this morning.

My name is Al Guida. I'm with Guide Consulting Services.

I'm here in behalf of, and solely on behalf of, Netsmart.

We are an electronic health record company that make EHR systems

for mental health and addiction providers, psychiatric hospitals,

community mental health centers, methadone clinics, and

residential treatment facilities for people with opioid addiction.

I want to just briefly discuss some of the technical issues in

conjunction with implementing the two rules that SAMHSA has recently issued on Part 2,

and we thank the agency for its regulatory activism to date in this area.

The rules rely upon a data segmentation infrastructure or

architecture whereby the patient with opioid addiction will go through their

medical record and identify pieces that they will be willing to share with

medical providers and those that they will not.

In order to implement both the rules and the data segmentation infrastructure,

SAMHSA developed an open source IT platform called Consent2Share.

Every hospital system, every primary care practice, every medical specialty practice,

every accountable care organization, every health information exchange in the United States

would have to adopt this open-source technology in order to be able to

operationalize the rules that Dr. Johnson discussed at the beginning this morning.

In order to do that, all of these providers have to modify their existing EHR systems,

have to train their staff on how to manage the consent requirements within the Consent2Share platform.

They have to train the individual with opioid use disorder on how to use the technology,

and there are apparently legal liability issues in conjunction with providing that training to the individual.

So, here's the outcome. An official with SAMHSA participated in the

Office of the National Coordinator annual meeting off of Dupont Circle in November 2017.

When asked with respect to how broadly Part 2 was being implemented, his response was, "Very low."

He was then asked about the number of hospital systems that have adopted the Consent2Share technology.

The answer was, quote, "Zero," end quote.

So, I think our concern, Netsmart's concern, is that with the inability to operationalize

Consent2Share, one of the key objectives that was described earlier,

permitting individuals with opioid use disorders to benefit from new care coordination programs and case management systems,

is defeated, and this is exemplified by the fact that the only two

health information exchanges in the United States, as far as we can tell,

actually accept addiction medical records.

One last thing: The last rule appeared to us to suggest that

SAMHSA use its discretion in separating out treatment and

healthcare operations from medical treatment and care coordination.

It's our view that an additional rule is necessary in order to be able to

unify these concepts so that addiction medical records can be shared in the

manner that was described a few moments ago to ensure proper treatment for

individuals with opioid use disorder that have a high incidence of comorbid medical/surgical

chronic diseases, HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C, cirrhosis of the liver, among others,

and also to ensure patient safety in prescribing both Vivitrol and buprenorphine,

which are FDA-approved products that have a pronounced contraindication profile

most prominently with benzodiazepines, anti-anxiety medication. Thank you so much.

MODERATOR (Suzette Brann): Thank you. Teresa Berman, Magellan Health?

TERESA BERMAN, MAGELLAN HEALTH: Thank you. I'm Teresa Berman, senior vice-president,

deputy chief compliance officer for Magellan Health.

On behalf of Magellan, thank you for hosting today's session.

My remarks will address the need for regulatory changes to Part 2 to

promote individual health, wellness, and recovery via improved care coordination.

Magellan's perspective on Part 2 is informed by our experience in

managing and administering mental health and substance use

disorder treatment and services for health plans, employers,

military and government agencies, Medicare and state Medicaid programs.

We also contract with more than 80,000 credentialed

behavioral health providers and provide services to 1.6 million government members.

For customers and members, Magellan performs case management,

care coordination, discharge planning, and related functions,

affording us significant direct experience with the impact of Part 2.

Much of what Magellan does on behalf of our customers and members

necessitates disclosing patient identifying information within the

healthcare system, interfacing and interacting with providers while

protecting privacy concerns of members with mental health conditions and often

occurring substance use disorders receiving treatment.

Indeed, the Journal of the American Medical Association found 50

percent of individuals living with a serious mental illness also have a substance use disorder.

As a result of Part 2's restrictions, these members' access to

whole-person fully integrated healthcare can be hampered when

providers are, in effect, prevented from accessing all relevant

information necessary to appropriately support his or her needs.

Magellan continues to urge SAMHSA to update Part 2 to align with

HIPAA by adapting a care coordination exemption to the consent requirement.

While HIPAA permits such information sharing for treatment and care coordination purposes,

Part 2 does not, presenting an unnecessary barrier and

marginalizing this crucial tool for individuals with substance use disorders.

This meaningful change would retain sufficient protection and

confidentiality of the individual's substance use records while also

bringing Part 2 into the modern era.

Part 2 was created before HIPAA existed, and these stringent

requirements are incompatible with contemporary advancements in care

coordination and electronic information sharing. The vast majority of today's integrated care models rely on HI

PAA-permissible disclosures and information to support care coordination,

that is, without the need for an individual's consent to

share relevant treatment details provider by provider.

Magellan believes it is critical for health plans to be able to

assist their members' recovery and relapse prevention by

sharing valuable substance use disorder information with

members' providers when we arrange for referrals, step-down services,

residential treatment, and other care coordination activities without the

need to obtain written consent for each individual provider.

The same is true for modern electronic infrastructure for

information exchange. In an era of electronic medical records,

having incomplete records available for providers because substance use disorder information cannot be

included without an individual's consent, it disallows

providers from supporting their patients holistically.

Providers are likely to believe the electronic medical record they

have access to includes the member's complete record.

In situations where this is not the case, a provider may,

for example, prescribe opiates for back pain for a member with a prior history of opiate misuse,

which could lead to a relapse.

Access to complete medical information is critical for providers to

ensure members' access to care is appropriate to their needs and their clinical histories.

To ensure individuals with substance use disorders receive the full

benefits of integrated care, Magellan respectfully requests the same care

coordination exception as contained in HIPAA be applied to information under Part 2. Thank you.

MODERATOR (Suzette Brann): Thank you. Is Amy LaHood, St. Vincent Hospital/Ascension here?

AMY LAHOOD, ST. VINCENT HOSPITAL/ASCENSION HEALTH: Thank you for this opportunity.

My name's Amy LaHood, and I'm a family doctor from

Indianapolis. I work for St. Vincent and Ascension Health

Hospital. I care for an underserved population and have done family medicine for the past 17 years.

I know firsthand the devastation addiction causes to families and in communities.

Two years ago, I chose to obtain my Suboxone waiver with the

intention of starting a perinatal opioid addiction program.

As a family doctor, it was obvious to me that doing prenatal care

alongside medication-assisted therapy seemed like an optimal

way to treat this vulnerable and motivated group of women.

I work at a church-shared care academic center and have the full support of hospital leadership.

I admit, I was naïve about the challenges in providing substance

abuse treatment in a traditional healthcare setting.

I've spent the past 12 months meeting with hospital leadership,

compliance, the best privacy attorneys in town, and our IT department.

I didn't even know CFR 42 Part 2 existed until two years ago.

My current EMR does not have the capacity to segregate data

within a single electronic space.

When our program starts this spring to be compliant with HIPAA and CFR,

I've been asked to simply have two simultaneous schedules for each

patient that comes in, to carry two separate laptops,

using two separate names and IDs in every patient room.

My nurse will have to do the same. In one electronic chart,

the information containing the prenatal visits will be kept.

In the other chart will be the information regarding substance abuse,

including urine toxicology results and the buprenorphine prescriptions.

The prenatal chart will be accessible to other providers in our traditional EMR.

The substance abuse treatment chart will not be available and will be

blinded to all other providers in my system.

This required blinding of substance abuse information is

counterintuitive to everything I'd envisioned in starting an integrated care model.

Today, most experts agree whole-person care is the optimal

framework to provide high-quality care. A patient's history or

current treatment of substance abuse is a vital part of their medical history,

and treating it differently perpetuates stigma of substance abuse.

Universal access to this information helps to provide safe, h

igh-quality care in order to minimize risk for future addiction and relapse.

Lastly, my understanding in doing opioid mitigation work is that CFR 42 is one of the reasons why

methadone clinics cannot or do not submit data to state prescription drug databases.

Treating providers have no mechanism to query whether a patient is on methadone.

Methadone is a complex, high-risk drug found in a disproportionately

high number of death toxicology reports.

Working to make methadone data available through state databases

will make patients safer and inevitably save lives.

I am here today to advocate for full alignment of CFR 42 with HIPAA.

I remain convinced this change will increase access to treatment,

reduce barriers to patients needing treatment, make care safer for

persons with substance use disorders, and potentially

allow integration of methadone data into state prescription drug databases. Thank you.

MODERATOR (Suzette Brann): Kelly Corredor, ASAM?

KELLY CORREDOR, ASAM: My name is Kelly Corredor, and I am the director of advocacy and government

relations for the American Society of Addiction Medicine.

ASAM is a national medical specialty society representing more than 5,000 physicians and

aligned healthcare professionals who specialize in the treatment of addiction.

I'd like to thank SAMHSA for holding this 42 CFR Part 2 Listening Session

and for its hard work on this issue to date. ASAM knows that the patient/physician relationship,

as the foundation of medical care, is often considered a sacred trust.

The uniqueness of this relationship derives from the mutual understanding that the encounter is confidential,

that what is said by each party is kept private from all others,

with exceptions for a listing confidentiality approved by the patient,

and the privacy of medical records documenting addiction treatment is especially important.

Part 2 is federal law that requires that documents of addiction treatment

be held to higher standards of confidentiality than even psychiatric records,

and far higher standards than records of general medical encounters.

With that being said, however, since Part 2 was promulgated in 1975,

dramatic changes have occurred both in (1) our healthcare system, and

(2) our understanding of the disease of addiction.

Today, the delivery of American healthcare is increasingly focused on

integration of medical services offered by different providers.

Disease management of chronic conditions, including coordination of

pharmacological treatment and recognition of the patients with the greatest needs,

those with multiple chronic conditions, are often associated with some of the

highest costs in the healthcare delivery system. Indeed,

the advent of integrated healthcare systems and electronic medical records

has improved the safety, quality, and coordination of care for patients with other health conditions.

Part 2 requirements, however, prevent patients with addiction from

sharing in these benefits, even though electronic exchanges of other

health information are governed by strict privacy and security standards

set by the Health Insurance Portability Accountability Act and the Health Information Technology for

Economic and Clinical Health Act.

Perhaps even more importantly, we have learned much about the

disease of addiction in the past 40 years.

Research has shown that we cannot effectively treat addiction in

isolation from other medical conditions.

Many psychiatric disorders, infectious diseases, and other chronic

conditions frequently co-occur with addiction.

Untreated addiction exacerbates these other conditions,

and untreated infectious or other diseases complicate addiction treatment.

As a result, ASAM has decided that the barriers that

Part 2 currently presents to coordinated safe and high-quality

medical care cause significant harm and that

thoughtful changes to federal law continue to be necessary to

mitigate this harm while protecting patient privacy.

Accordingly, ASAM has joined other provider associations, patient groups,

and health plans to support legislative efforts,

which would align Part 2 with HIPAA for the purposes of healthcare treatment, payment, and operations.

Such a change would allow for the sharing of patients' addiction treatment records within the healthcare system

under HIPAA's well-established and modern privacy and security protections,

while leaving in place Part 2's prohibition on disclosure records

outside the healthcare system.

Moreover, we could use such a legislative opportunity to

strengthen protections against the use of addiction treatment records in

criminal and civil proceedings as a further improvement to Part 2.

In conclusion, ASAM will continue to advocate for the highest treatment

standards and the most compassionate care for patients with

addiction and seeks to hasten the date when all our patients can

easily access state-of-the-art treatment and a healthcare system and a world that do not stigmatize their disease.

And despite all good efforts to date, further targeted changes to

Part 2 remain necessary to realize this goal. Thank you for listening.

MODERATOR (Suzette Brann): Joycelyn Woods, National Alliance for Medication-Assisted Recovery? Joycelyn Woods? William Stauffer, PRO-A?

WILLIAM STAUFFER, PRO-A: Good morning. Thank you for the opportunity to speak today.

My name is William Stauffer. I'm the executive director of the Pennsylvania Recovery Organizations Alliance,

a statewide recovery organization of Pennsylvania.

I'm a licensed social worker,

I have 25 years' clinical experience, and I'm also a person in long-term recovery,

31 years in recovery.

I'd like to start by saying I'd like to live in a world where substance

use conditions are like other medical conditions.

They are not. We are not treated the same, whether we're an airline pilot,

a pharmacist, a physician, or a licensed social worker.

When we acknowledge that we're in recovery or have an addiction problem,

we are treated differently, and we are subject to discrimination.

It is important to note that my first question when I walked into a

treatment center in 1986 at the age of 21 was about confidentiality

and what was going to happen to the information I shared with my counselor.

I trusted the answer I received back then.

I know now that such trust is critically important to the fragile therapeutic

alliance that must develop for a person to get better.

The final rule, as it stands, endangers this fragile therapeutic alliance

and may well reduce access to care as a result by making access

and use of our information unknowable to the patient.

Recent changes to the rules make informed consent virtually impossible.

Information can now go in a myriad of directions once released.

If the information is used to discriminate against us,

it's impossible from the patient's perspective to know where the violation occurred and who did it.

The best example of this is under the use of payment and healthcare operations,

which is described in the final rule, and I don't have the time to read

through that list of 17 things. Given that long list, as a treating

clinician, I would have to tell the client that I have no idea

who will get their patient information or how it is used.

Under this rule, I would've not entered treatment, or I would've s

elf-edited my disclosures in such a way that it would undermine my own care.

I'm not alone in that. I was talking to an airline pilot the other day that

I had to assure multiple times that the information that I shared would not go beyond that.

Such a person could still be flying planes I'm flying tomorrow. I think about that stuff.

Please understand that there is much greater stigma around

substance use conditions than other kinds of medical conditions.

The very acknowledgment of having a substance use condition

can open us up to discrimination and, in many instances, place us in legal jeopardy.

We face a Hobson's choice when confronted with a consent to release our information under the current rule.

We implore SAMHSA to not further weaken our confidentiality rights.

We are concerned that these changes add many layers of complexity and

ambiguity to the regulations and will only serve to create further confusion.

It is worth noting that many care professionals do not understand

that they can access information with a properly executed consent,

while others seem not to care to be bothered to honor our privacy rights.

We understand that SAMHSA is seeking balance between protecting

confidentiality of substance use disorder patient records and

those who would wish to have expanded access to our personal information.

The bottom line is that if consent to release our highly personal

information is required for payment or to participate in treatment,

we're left with no real choices beyond avoiding care or risking the

use of our information to discriminate against us after it flows into our medical records.

We respectfully request that any additional rulemaking would be used to

protect us from misuse of our information and to hold those who

would use it to discriminate against us as accountable to protect our information.

It is the standard that Congress strived for back in 1972, which we

believe is just as relevant now, and I will read that:

"The conferees wish to stress that their conviction that the strictest

adherence to the provision of this section is absolutely essential to the

success of all drug and alcohol abuse prevention programs.

Every patient and former patient must be assured that his right to privacy will be protected.

Without that assurance, fear of public disclosure of drug abuse or of records that…would

discourage thousands from seeking the treatment they must have if this tragic national problem is to be overcome."

We staunchly believe that sharing of addiction and recovery information is an individual choice to be made by the individual,

who retains control over who gets it and how it's used.

We think that this is a fundamental right and important to quality care and consistent

with the original statutes, and we ask that the original intent be

honored under the regulation. Thank you. [END OF VIDEO TWO]

For more infomation >> First lady's gravesite opens to public - Duration: 2:19.

For more infomation >> First lady's gravesite opens to public - Duration: 2:19.  For more infomation >> New Haven Alder to host public forum on marijuana legalization - Duration: 0:26.

For more infomation >> New Haven Alder to host public forum on marijuana legalization - Duration: 0:26.  For more infomation >> Ethics, Citizenship, and Public Responsibility - Duration: 4:13.

For more infomation >> Ethics, Citizenship, and Public Responsibility - Duration: 4:13.

For more infomation >> Newest Royal Baby Makes Public Debut - Duration: 1:29.

For more infomation >> Newest Royal Baby Makes Public Debut - Duration: 1:29.  For more infomation >> Parents protest 'graphic' sex ed taught at public schools - Duration: 2:30.

For more infomation >> Parents protest 'graphic' sex ed taught at public schools - Duration: 2:30.  For more infomation >> First lady's gravesite opens to public - Duration: 0:31.

For more infomation >> First lady's gravesite opens to public - Duration: 0:31.  For more infomation >> A Public Service Workforce for the Future - Duration: 1:31:37.

For more infomation >> A Public Service Workforce for the Future - Duration: 1:31:37.

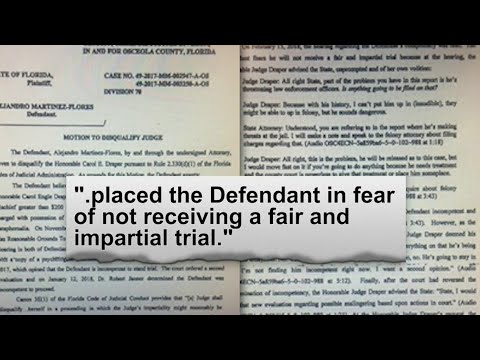

For more infomation >> Public defender wants Osceola judge disqualified - Duration: 2:00.

For more infomation >> Public defender wants Osceola judge disqualified - Duration: 2:00.

For more infomation >> Governance Challenges and the Future of a New Public Service - Duration: 1:05:15.

For more infomation >> Governance Challenges and the Future of a New Public Service - Duration: 1:05:15.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét